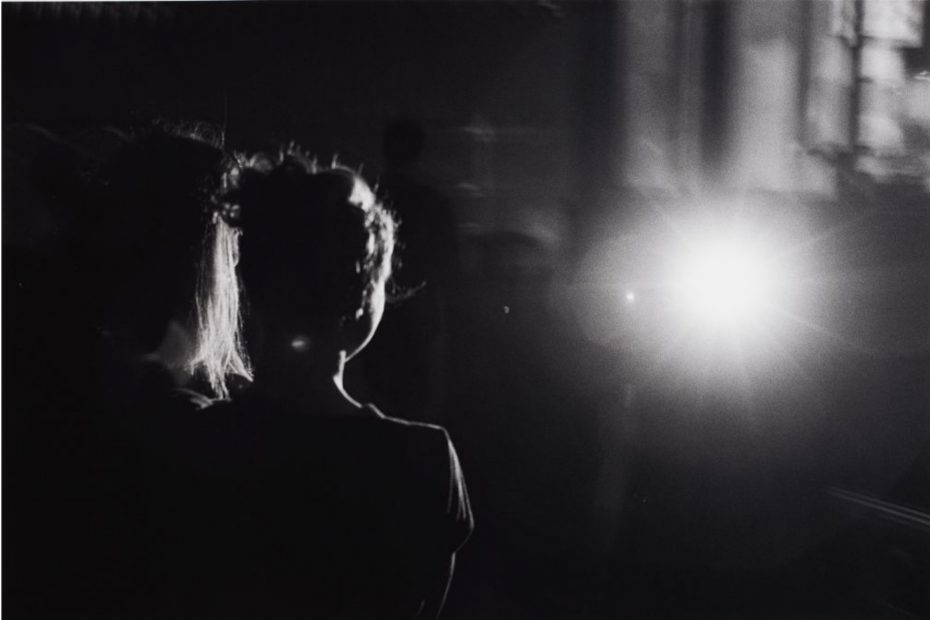

Harvard Art Museums, on view through 8/12/18. Featured image, John Schabel: Night Shot 6, 2001.

by Joel Howe

“Analog Culture” displays a selection of artist-proof photographs from the collection of Gary Schneider. In the 1970s, ’80s and ’90s, Schneider collaborated with many well-known photographers to produce hand-printed editions of their work at his Manhattan photo lab, Schneider/Erdman. Typical of the industry, he saved one artist-proof print from each collaboration for his personal collection.

The exhibited photographs date mostly from the 1980s and 1990s—the heyday of Postmodernism, with its emphasis on marginalized subjects and meta explorations of the act of image-making. The show contains many influential names from that time period: Nan Goldin, David Wojnarowicz, Lorna Simpson, Peter Hujar.

Rather than any thematic content, the three-room exhibition is organized around the creative collaboration between artist and printer and the expressive techniques of darkroom printing. Consequently, and by design, it has a somewhat random feel, with the various artists’ photographs ranging wildly in subject matter and aesthetic style.

Some of the Stand-out Images

While I found myself somewhat frustrated trying to make connections among the subject matter of the different photographers, many individual images stood out.

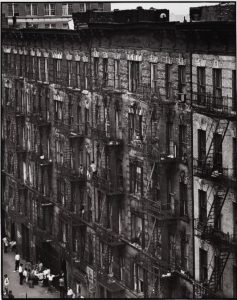

Bruce Davidson’s East 100th Street Façade is a massive print of unfolding city drama: a foreshortened rooftop view looking down along a long row of brownstone facades. Various social interactions play out at different levels—through the windows, on the fire escapes, upon the stoops and at the sidewalk. The print is high contrast, dark and brooding, emphasizing the stage-like quality of the unfolding drama.

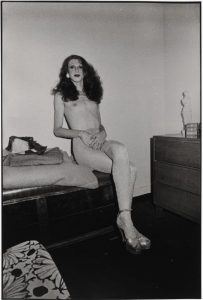

Nan Goldin’s Marlene at Home with Venus de Milo is a harsh flash-photo portrait of a drag-queen, leaning back into the corner of the room. Printed dark with no highlights to speak of and hardly any contrast, it emphasizes the dinginess of the space and an overall sense of isolation.

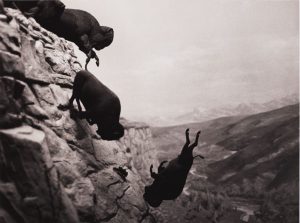

David Wojnarowicz’ Untitled (Buffalo) is an arresting image of several bison tumbling over a cliff edge. Soft-focus and printed on a warm-tone paper, it stylistically evokes the old American West images of Edward Curtis. The dreamy quality to it reveals upon closer examination that the photo was made in a natural-history museum diorama.

The Ascendance of Digital

The final room of the exhibit contains the following anecdote, intended to illustrate the eventual supremacy of digital printing over traditional darkroom silver-printing:

“The artist Robert Gober brought a digital file into Gary Schneider’s lab, asking to have an edition produced of analog darkroom prints. The photo was a small, closely-cropped image of an ear.

“Attempting to perfectly match the digital file, Schneider labored over the assignment, first producing a film negative to use in the darkroom enlarger, as well as additional ‘masking-negatives’ of the highlight and shadow areas of the image, intended to bring out subtle details and tame the high contrast of the ‘original’ digital photograph. [All three negatives are displayed in the exhibit on a light-table.]

“Despite Schneider’s best efforts, the endeavor was ultimately a failure—the original digital file better represented Gober’s vision and he eventually gave up on the idea of producing an analog version, choosing to print the edition instead with a digital inkjet printer. Schneider/Erdman’s lab shuttered its doors not long after this episode.”

Digital has won out. Or has it?

Is there still a place in the fine-art photography world for traditional handmade darkroom prints, or are the last holdouts simply beholden to nostalgia?

These questions came to mind while viewing the exhibit, as I am a photographer who still shoots film and makes darkroom prints. What is the reason to struggle in the darkroom, inhaling chemical fumes and wasting sheet after sheet of expensive gelatin-silver paper, trying to make a perfect print, when a single click of the Auto-Contrast button in Adobe Photoshop can produce an inkjet print with impressive tonal range?

I was an art school student of photography in the 1990s, and Schneider’s masterfully printed photographs did indeed evoke feelings of nostalgia for me, especially since the exhibit labels included additional details such as the brand of darkroom paper used, most of which have subsequently been discontinued.

Ah yes, I remember the good old days of Kodak and Agfa paper, the soft warm tones of Portriga Rapid… It occurs to me that some younger photographers who may have never stepped foot in a darkroom will respond quite differently to this exhibit.

A photograph by Peter Hujar caught my attention on my way out of the exhibition: a portrait of his dog, “Will,” a Shar-Pei breed. Made in 1985, when Hujar was battling AIDS, the image portrays Will staring into the camera while posing heroically atop a podium; his voluminous folds of skin merging seamlessly into the soft folds of velvet upon which he sits.

Printed on Agfa Portriga paper, known for its warm tones and rich velvety blacks, the print has also been “dodged” in the darkroom to lighten the dog’s face, resulting in somewhat of a halo-effect that emphasizes the majestic pose.

Perhaps an equally striking image could have been produced by digital means, but this hand-printed photo of a dog seemed to me a fitting rejoinder for the continued relevance of “Analog Culture.”

Joel Howe is an architectural and fine-art photographer based in Cambridge, MA. He also edits and maintains the Calls for Entry feature of the PRC website.